THING 022 : ASYMMETRY

JAMES MÆSSIAH

JULIAN OSTI

INABILITY TO EXPRESS GRATITUDE (2011, 2024)

ALEX ASPDEN

PENSIÓN

cicada sallies out on bedside table from under crust-faded pink lampshade. time/method of entry unknown, window closed despite heat since arrival in hotel room though can’t call it that[1] one/two weeks ago (i have not eaten). likely present on arrival but secreted in silence no doubt struggling against all-consuming impulse to chirrup[2]

[2]chirrup now mid-release but unheard through headphones not taken off since arrival. lying on bed (haven’t slept) watching cicada let out pent up drowsy scream under diffuse pink light like a lounge singer on stage under equally gaudy luminosity

[1]the wall behind the sink where i must piss to avoid[3] the shared bathroom/other guests[4] flecked with yellow where pissers before me have likewise declined sociality. shade and fading denotes antique and recent piss but flecks and streaks at highest elevation near ceiling too high to be closely inspected. such elevation achieved only and presumably with built up pressure from extended and presumably damaging periods of piss retention

[3]avoidance extended not only to guests but also to hot citric city beyond hotel walls stepped into just once when transiting from airport to hotel. in the street voices and sounds projecting malleable threads through air forming huge crisscross network from mouth to street to district town region country continent along railway road sea air space and planetary systems before returning to the mouth that issues a single no thanks to all ultimatums to participate

[4]other guests unseen unheard behind thick walls of this pronunciamento-era building silent under headphones[5] total ambient exclusion god bless

[5]12-hour drone track playing uninterrupted from phone charging[6] nonstop since arrival solely to keep track streaming 24/7 except since last night unplugged and moved to increasingly inaccessible positions until deposited under loose floorboard lifted placed closed stamped down to render phone permanently gone. its alchemic powers of distraction once comforting or diverting suddenly and without explanation alien and unwanted

[6]to be reinserted into unfortunate presence of self[7] when battery runs out

[7]not another soul[8] seen since entering lobby from street on arrival at this cheap pensión the graffiti in the lobby not just eviscerating texture of blank space but hypnotic in its invocation of ancient deities even to the wilted monstera in the corner stained with disease but reaching branches/leaves towards it in sickly devotion. apparently find myself at such peace at night that when eyes closed in elevated consciousness i not only emulate monstera in twilight devotion but become it with legs and lower half potted top half shirtless and diseased reaching towards ancient symbols

[8]not another soul minus front desk woman with bed and hotplate visible behind desk our exchange the pure essence of failed words streaming out[9]

[9]preferred exchange (didn’t occur): indefinite stay, single room, shared bathroom, 110 euros, same next week, signature, passport[10]. instead (occurred): hundreds of unordered verbal formations melting together lapping each other and she wincing at each word entering her auditory consciousness

[10]still remain person depicted in passport and that person lingers despite coming here[11] to be not that person but now finding them unextractable even with headphone drone/mind rested. ending the silence before it ever was and now failure to recover what never was despite entering of elevated states invoking deities with genitals neatly cushioned in potting soil[12]

[12]with the struggle to reach deitic (leaves reaching) states of concentration in the presence of unknown gods i turn without reversal away from flesh to leaves and terminally diseased cells without ears eyes or mouth

[11]coming here on a plane[13] breathing unspoiled air from metal belly

[13]before stepping with human legs in sorry and retained physical form into the street alive still one active node in network of voice and conscious impression until cloistered in pensión with cicada[14]

[14]becoming a network of one/an untouchable absence[15]

[15]living forever as pure/sick foliage[16]

[16]withdrawing expressly to

live forever[17]

[17]with leaves reaching (so to speak)

EMILY ALLAN

PERFECT BRAIN (CLANGING)

ALAN MARTÍN SEGAL

FOLEY

CORO

ZACH HUSSEIN

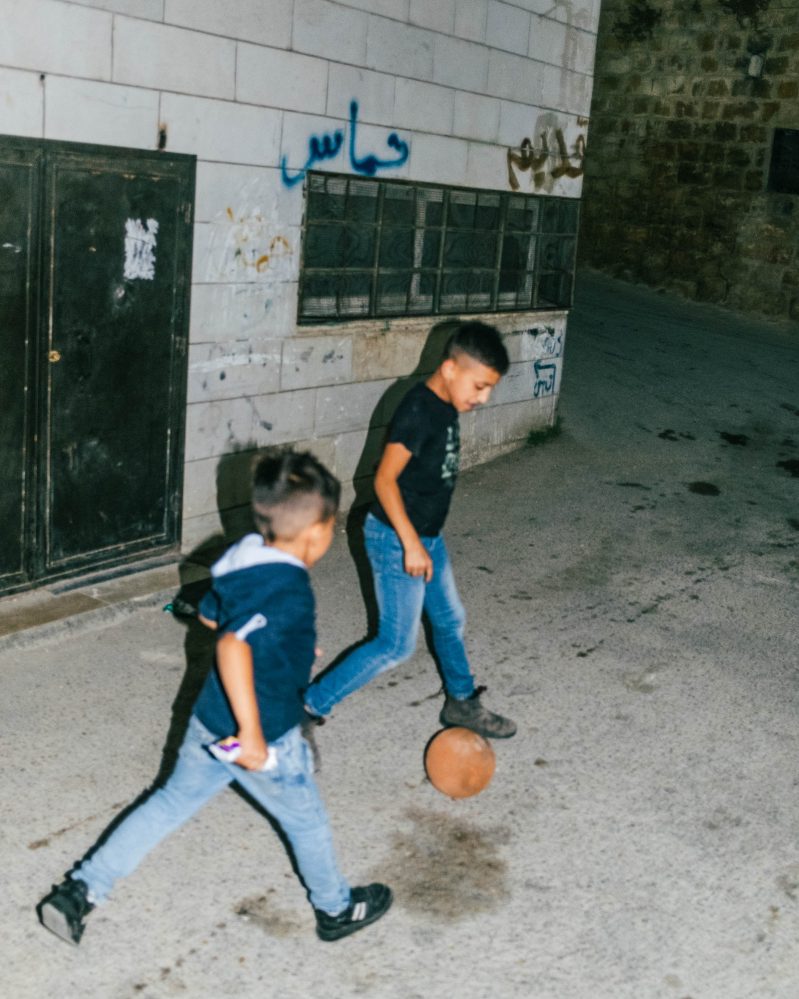

WHEN WE RETURN

Some of my earliest memories revolve around my mother screaming at Israeli soldiers to let me and my brother back across the King Hussein Bridge from the occupied West Bank to Jordan. She begged and pleaded for them to let us across but they’re Americans! The Israeli soldiers didn’t care, yelling: They’re Palestinian now. We eventually were able to return after a few more days in the West Bank, but that experience stuck with me. I recently found out from my father that my Siedo, who was with us at the bridge, smiled and crossed back into Jordan after he heard what the soldier said. They’re Palestinian now.

The stories of Palestine that all of us in the nearly six million strong diaspora are told never left my consciousness. Stories of the beauty of the land, of long-standing defiance in the face of a bloodthirsty colonizing force, of the sadness of being forced from your land or the bravery of the martyrs, all of it influenced how I thought about and saw my homeland. Family members would call me in efforts to dissuade me from going. You won’t like it // it’s not what you think // it’s not safe. But when I was finally able to return for the first time as an adult, it was an even greater experience than I could have imagined.

After a 40 minute taxi from my Tayta’s apartment to Al-Karameh and then hours at the various checkpoints that make up the King Hussein Bridge, I was in Palestine. But this currently palatable (to the occupiers) idea of return isn’t one granted to all Palestinians. With the way Zionists have divided Palestinians, many won’t be able to return until liberation. Whether in refugee camps located in the surrounding Arab states or simply unable to visit with whatever citizenship was obtained after the Nakba and Naksa, for a lot of Palestinians returning is a multi-generational dream. Even within Palestine as it is now (occupied) many are unable to see their hometowns, trapped in a complex maze of different identity statuses (green // blue // Jerusalem // Gaza) and under a complete illegal military occupation. Because my Siedo had gotten my brother and I hawiya’s, the green West Bank IDs that only allow for travel within the West Bank and only certain areas at that, I have been able to live a fragment of a collective dream for the future; I was able to return.

When I was in Palestine, my uncle told me that he had never seen somebody so happy. I felt at home somewhere I had never really been before. The quarries carved into the mountains, peaked with olive groves and dotted with homes on the land that my family has lived in for centuries is a sight I will never forget. Jemma’in was glowing. Every boulder, olive tree, flower, or piece of dirt is Palestinian. Even the trash. The food you eat is more tasteful, the colors of the soil and sky are brighter and the air just better. Despite the drones buzzing overhead and settlements in the (not far) distance, you are home – My Siedo always said that the settlements cowered at the top of mountains, far out of reach. Our villages, however, were always in the valleys, embraced by the Earth and the land.

My Tayta is from Al-Falujah, a village close to Gaza that only exists in the memory of its inhabitants. Now only ruins and a settlement: “Kiryat Gat.” There is nothing to return to except the land and an Intel factory. For many Palestinians, this is also their reality. More than 500 villages were destroyed by Zionist forces in 1948, and though I am fortunate enough to have a village to return to, returning there isn’t what it should be. Throughout every step of my time in the West Bank, it is absolutely apparent that it is occupied. Occupation forces man checkpoints (at every intersection). In Ramallah, the blown out walls of an apartment are all that’s left after Israeli forces came in the middle of the night and collectively punished an entire block. Homes covered in the flags of various political groups signify prisoners who had finally been able to come home. Posters on nearly every wall show the faces of the martyrs who weren’t able to. In the Old City of Nablus, bullet holes and explosive damage decorate the faces of shops and homes. Young men point to the posters and then point to the burnt-out moped, the bloodied Palestinian flag, the bullet holes in the wall, the blown out window and show you where their close friend was murdered by Israeli forces, just a few days ago. Roads are randomly closed because settlers decided we cannot go there. In Al-Bireh Israeli police shoot at us, hitting young men behind us as they were throwing molotovs, resisting the occupation forces as they were (again) invading and causing (another) bloodbath in Jenin. Massive walls with guard towers and fortifications bisect our own cities, on our own land. A checkpoint needed to (illegally) see our own capital.

On that night in Al-Bireh, my first in Palestine in 14 years, my uncle and I spotted young men throwing stones and molotovs into the night. You wouldn’t know it from how carefree the young men were acting, but less than a hundred meters away there were Israeli forces aiming at us. When the occupation forces eventually shot back, they hit a young man in the leg. Despite his screams, nobody seemed bothered. One of his friends helped him to the ambulances who had been waiting for the inevitable casualty. But even as another young man was hit in the leg, there were still crowds, guys just hanging around on their bikes, talking and laughing. Unfazed. We are programmed to be okay with the violence that Palestinians are ceaselessly forced to endure. October 7 changed everything, but also it didn’t. I remember waking up in the morning of the 7th and being told that 200 Palestinians had been killed (then 5,000 // 10,000 // 20,000 // now 30,000 // maybe 40,000?). It’s sad that my response wasn’t more than “yeah, it happens.” Then they told me that 2,000 Israelis were dead. That was unexpected. Palestinians are always being murdered and blown up. When I hear that someone we know was martyred or that there was a shooting operation in the village next to ours and the soldiers are tearing through our family apartment searching for the assailant, it’s business as usual. The horrific retaliation for October 7th is yet another entry to massive loss of Palestinian life in a list that’s all too long. But it’s different.

I have never seen people I know come together like they are now. Fighting back in the streets of Ramallah, Gaza City, Jenin, Amman, Damascus, Beirut, and even here across the United States. Fighting back against the genocide that Palestinians have long been faced with, but now suddenly aware. Despite the horrors coming out of Gaza everyday, people feel hopeful in their mourning. My Tayta proudly showed me her red triangle necklace. For hours, she’s sat across from the T.V., watching Al-Jazeera’s analysis of the latest ambush against Israeli forces in Gaza. She hasn’t been to Gaza since 1948, and now she sees it in ruins again. But this time it’s different. She’s cheering. People are seeing the cracks. Even my Tayta. 76 years away from home she has hope.

I was born in the U.S. and raised with few Palestinian people in my life. Still I dreamed, still I returned. With every one of us that hopes to see our land, to walk on it, to embrace it, we strike fear into the heart of their “project.” Just like the tens of thousands of Palestinians like me in the U.S. and across the globe who have been taking to the streets in support of their occupied homeland. None of this fits their canon. We should’ve forgotten by now, three generations and oceans away from the trauma of 1948. But we won’t. The land is more beautiful, more alive, than any of the stories we are raised on. I was fortunate enough to experience just a glimpse at what a future might be, where all Palestinians can come home. Returning will not be easy. It will not be clean. But it will be our future. We will return.